Near the end of 2001 no fewer than three urban malls opened their doors to the shoppers of greater Los Angeles. These malls – and at least another three are in the final stages of construction or planning – represent a prodigious production of retail space, over 4 million square feet of shopping. Moreover, their scale, density, and architectural typology is also stunning, and unprecedented since the opening of the notorious BeverlyCenter in 1982. [1] As perceived by the popular press and consumers, these malls represent a reinvestment in the city as a social and economic site – Hollywood & Highland is the keystone for the LA Community Redevelopment Agency’s revitalization of Hollywood Boulevard, and a civic center plan commissioned by the City of Pasadena dictated the urban configuration of Paseo Colorado. For others, these malls signal the final capitulation of the city to suburban cultural and economic norms. These critics attack the homogenous mixture of national and global retail chains typical of any high-rent, centralized management structure. Yet beyond the proliferation of Baby Gap and Banana Republic, the creeping suburbanization of urban malls indicates a shift of a more systemic nature – one that significantly diminishes the palette of urban design tools and, more disturbingly, reduces our understanding of urban life.

Of the three malls, The Grove most clearly illustrates these issues, particularly because its adjacency to the venerable Farmers Market at Third and Fairfax amplifies the history and future of the urban shopping mall. A visit to both the Market and The Grove reveals strikingly different spatial experiences. The former is a semi-enclosed, claustrophobic labyrinth of small shops, housed in anonymous agricultural shacks and set on an asphalt parking lot. The newer mall is more like Main Street Disneyland or the Forum Shops at Caesar’s Place in Las Vegas, albeit without an artificial sky or animatronic fantasy figures. The Grove’s medium and big box stores and multiplex cinema face a central open-air walk and are housed in vigorous reproductions of historic commercial architecture, detailed throughout in materials luxurious for a shopping mall. Only a set of mid-sized buildings by the Market’s architectural stewards of twenty years, Koning Eizenberg, mediates between its one-story casualness and the three-story deliberations of The Grove and its massive, computer-monitored parking garage. [2]

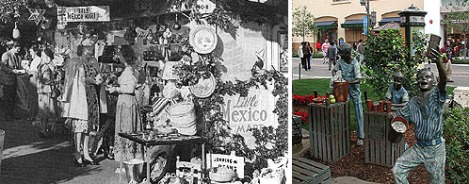

Yet the gap between the two is bridged with a straight line for the Market is essentially the prototype for the suburban shopping mall and The Grove is its most current incarnation. Although its relaxed attitude suggests the Market was an outgrowth of ad-hoc gatherings, its rural aesthetic was a calculated marketing strategy not so different from the Mexican stylism of its contemporary at Olvera Street. The unique environment of the Market was designed to encourage leisure shopping. “With little outlay, a bazaar-like atmosphere was cultivated to enhance the experience so that shopping for food would seem more akin to a leisure than a routine pursuit. Fueled by an aggressive advertising campaign, the Farmers Market began to attract an affluent trade of movie stars and others who sought the unusual goods sold there and took pleasure in the novel ambience.” [3] The historicist imagery of The Grove engages in the same manipulative choreography, albeit updated by seventy years of market research and with architect Jon Jerde as mediator. Less skillfully executed than a Jerde Partnership “experience”, such as San Diego’s Horton Plaza or Universal CityWalk, The Grove’s narrative architecture and programming clearly owes much to their innovations. [4]

Yet the fundamental innovation of the Farmers Market is that unlike the shopping courts of its day it has no retail street frontage, but is an internalized court located in the middle of a parking lot. This typology, of course, would become the dominant model of late twentieth century shopping malls. In Los Angeles, Lakewood Center was the first mall to conform to this now-classic model, firmly established by earlier structures such as Seattle’s Northgate and Boston’s Shoppers World. [5] The juggernaut of this type is now the 4.2 million square foot Mall of America outside of Minneapolis, although the title of world’s largest mall once belonged to 3+ million square foot Del Amo Fashion Center in Torrance. In the transition from the Farmers Market to the Mall of America stands late modern architect Victor Gruen, the father of the modern shopping mall. Gruen organized the parking strategy and pedestrian-only environment of the Market with economic proformas of department stores and the technical innovations of modern architecture and transportation planning into a codified formula for producing suburban shopping malls. [6] Over the next twenty-five years, the regional mall quickly became one of the most recognizable architectural and marketing typologies in America suburbia. [7] Inevitably, as retailers rediscovered the city, the suburban mall was imported to the city. Although surface parking generally does not surround urban malls cars are located under the mall as at Century City or next door in gigantic parking garages as at The Grove the spatial organization remains decidedly suburban. Even if the roof has been removed, opening the mall interior to the sky, shops and pedestrian passages remain focused inward towards privately controlled “public” space, disconnected from the street life of sidewalks.

But as the penultimate evolution of the mall, The Grove is neither innovative nor particularly imaginative. For architects, the dilemma of The Grove is not its postmodern pastiche of architectural styles, but its failure to expand the mall’s range of typological or urban performance. More troubling, The Grove’s popular success also reinforces entertainment retail (retail-tainment) as the only legitimate activity for creating urban places. The dominance of shopping exacerbated in California’s sales tax addicted cities establishes retail centers as the only tool of urban design, to the exclusion of production (the workplace) and living (housing), and at the expense of a sustainable urban economy founded in a physical form that balances land uses with transit needs.

For a divorce between consumption (represented by shopping / entertainment) and the productive, domestic, or civic / political life has occurred during the evolution of the Farmers Market to The Grove. At The Grove, shopping has no connection to the surrounding Fairfax neighborhood, or even to greater Los Angeles. Whereas the Farmers Market married rural agricultural production with urban life at the local scale, the corporate enclave of The Grove, like most malls, is occupied by branch stores of national retail / entertainment corporations, with little relationship to the industry of the city. Shopping at The Grove does not prime the economic engine of Los Angeles manufacturers or retail companies. [8]

Although the Market’s connection with local production was quickly lost as its architectural typology was applied to regional shopping malls, malls briefly retained elements of local civic culture. Gruen viewed the shopping mall as the suburbs’ social center, and the inclusion of local cultural and political establishments was integral to his early mall formulas. Yet for the most part, even storefront post offices are absent from major shopping centers. In its place, The Grove features two European-feeling pedestrian streetscapes that converge on centralized park, with a small pond and actual grass. Although it is essentially an outdoor version of the atrium typical of suburban malls, including its set-to-music water fountain created by WET Design of Bellagio Vegas fame, this park nonetheless is immensely popular. Yet this very popularity makes The Grove that much more problematic. In one corner of the park is a collection of bronze sculptures, representing a gaggle of (white) children in 50’s attire selling lemonade. At Christmas, the park features a gigantic fir tree which signage proudly explains is taller than the Rockefeller Center tree. The references to the Rockefeller Center and mid-century Americana symbolically equate The Grove with the archetypal public green of New England villages and the democratic, urban civic culture such archetypes carry. But The Grove is entirely private space, created, owned and governed by Caruso Affiliated Holdings. Its primary and only purpose is shopping and entertainment: public facilities and institutions associated with democratic government are absent; offices and workshops of middle-class and working-class labor are not to be found; and the products of regional businesses are not sold here. The congested popularity of The Grove and its architectural and decorative symbolism gives it the appearance of a vibrant, rich urban place yet it is ultimately a place where urban life is rendered in one-dimension, reduced to consumption only. The simulated city is just a marketing tool to amplify sales-per-square-foot numbers. This concentration of hyper-consumerism is not a problem per se – after all, commerce constitutes a certain kind of “publicness” and is one of the city’s primary functional reasons to exist. Rather, the problem is that within popular perception The Grove’s success quietly and insidiously eliminates other possible definitions of urban life, leaving architects and developers only one option for activating the city: shopping

Meanwhile, The Grove is hidden from Pan Pacific Park by its massive parking garage and presents a blank wall to the real public face of Third Street. The architectural cinema of The Grove’s interior is not directed towards the sidewalk and none of its storefronts open on the street. The urban design of The Grove does nothing to positively contribute to the pedestrian life of Fairfax’s streets – it merely increases traffic. One suspects Byzantine conventions and the machinations of retail real estate played a greater role in shaping the disposition of The Grove than LA City planners, who should have rejected its “Berlin Wall” as a matter of course.

The Grove’s defiant rejection of Los Angeles’ streets is all the more distressing because of the latent transformative effect LA’s commercial corridors could have in solving the region’s planning challenges. Beginning with Doug Suisman’s 1989 Los Angeles Boulevard pamphlet, the under-performing commercial mileage of Los Angeles boulevards has been viewed in the context of a cataclysmic housing shortage, no-growth single-family neighborhoods, and the prospect of transportation gridlock. Suisman and others have argued that LA’s boulevards are the optimum site for mixed-use corridors combining high-density housing, sidewalk pedestrian-oriented retail, and, critically, either bus-way or fixed-rail transit lines. [9] From this ideological perspective, it is sadly ironic that The Grove’s “streets” feature a double-decker, state-of-the-art electric-powered trolley to transport shoppers from the parking garage to the Farmers Market. Meanwhile, a mid-density residential development, similar to many others appearing across the city, is nearing completion across Third Street, yet the relationship between housing and retail seems to have been given no thought by either the designers of The Grove, of the housing development, or the planners charged with imagining the City’s future. [10]

Yet there are alternatives to The Grove: commercial projects by mainstream developers that incorporate ground level, street-facing retail with upper-level condos or apartments – Paseo Colorado in Pasadena, Hollywood/Western in Hollywood, and CityPlace in Long Beach. Of course, none of these three projects represent an ideal model. Half of CityPlace’s sidewalk frontage is service yards and parking garages, including that facing the adjacent Blue Line light rail stop; the clunky brown and orange stucco detailing of Hollywood/Western is simply ugly and garish, even by Hollywood standards; and Paseo Colorado retains internalized shopping courts while its architecture is deadly flat and uniform, as if it were a full-scale enlargement of a cardboard model. [11] Nonetheless, each of these three malls has partially turned the conventional typology of the mall inside-out and upside-down: storefronts face the sidewalk and the airspace above the stores is occupied by housing. As architectural prototypes, they inject new imagination into the standards of large-scale urban shopping centers. As urban design, they are part of broader strategies to increase the residential density of traditional office/commercial cores with an aim towards creating the proverbial 24/7 city. [12] As financial propositions, they also seem to be meeting early success: Paseo Colorado was recently sold at a considerable profit to its original developer. [13] Certainly the mythical days of shop owners living above their wares are over, but neither do these recent projects promote that myth. Rather they suggest that, although just opened, The Grove is already an obsolete model for the mall. For The Grove is nothing more than Fairfax’s version of CityWalk, incorporating its spatial choreography, but also its isolation as a destination. When exhausted as an entertainment destination (for assuredly something newer will come along), its single-purpose architecture will be obsolete, like its “dead mall” predecessors on the suburban fringe. Although the Pasadena, Hollywood and Long Beach projects share many of The Grove’s stores and therefore engage in the same consumerist fantasies, they are constructed in an architectural form that responds to the city’s present social dilemmas, yet is adaptable to incremental change, where storefront tenants will reflect the evolving nature of the city’s street life. As such, they represent a more sustainable investment of city’s resources and its long-term future. With their mix of residential and commercial uses oriented towards the city’s sidewalks and suggestion of transit corridors on boulevards, these projects are the first gestures towards the future of the mall in Southern California.

[1] The three malls are, of course, Hollywood & Highland at 640,000 sq ft, The Grove at 575,000 sq ft, and Pasadena’s Paseo Colorado at 565,000 sq ft. Also open or in development at the beginning of 2003 is West Hollywood Gateway at 245,000 sq ft, Long Beach’s Pike at Rainbow Harbor at 369,000 sq ft, The Promenade at Howard Hughes Center at 250,000 sq ft, Sunset Millennium in Hollywood at 200,000 sq ft, Pasadena’s The Shops on South Lake Avenue at 150,000 sq ft, and the reconstruction of Long Beach CityPlace at 500,000 sq ft, Sherman Oaks Galleria at 300,000 sq ft, and Santa Monica Place at 278,000 sq ft. The Beverly Center is a whopping 876,000 sq ft.

[2] Carolyn Ramsay, “A Market Fresh Look”, Los Angeles Times, 03 Jan 2002 and Koning Eizenberg Architects.

[3] Roger Dahlhjelm established The Farmers Market in 1934. Olvera Street (formerly Olivera Street) opened in 1930, thanks to the efforts of Christine Sterling. (Richard Longstreth, City Center to Regional Mall, MIT Press, 1997, pp 279-283.)

[4] The rooftops and HVAC equipment of The Grove can be seen from the upper levels of its parking garage, a lapse in the coherency of the design/fantasy narrative that one would not expect of the Jerde Partnership. For more on Jerde, see Frances Anderton, editor, You Are Here: The Jerde Partnership International, Phaidon Press, 1999 or http://www.jerde.com. For more on the narrative design of The Grove, see Morris Newman, “The Grove’s Groove” in Grid, May 2002.

[5] Lakewood Center opened in 1952, Shopper’s World in 1951 and Northgate in 1950. (Richard Longstreth, City Center to Regional Mall, MIT Press, 1997, pp 332-333.)

[6] Victor Gruen and Larry Smith, Shopping Towns USA: The Planning of Shopping Centers, Reinhold Publishing Corporation, 1960.

[7] Peter Rowe, Making a Middle Landscape, MIT Press, 1991, pp 109-147.

[8] The Farmers Market was established to sell local produce. (Richard Longstreth, City Center to Regional Mall, MIT Press, 1997, p 282.) Some might argue that the cinemas at The Grove are outposts of the local film industry. Considering that marketing and finances of cinema makes little variation for local circumstance, I do not find this convincing.

[9] Doug Suisman, Los Angeles Boulevard: Eight X-Rays of the Body Public, Los Angeles Forum for Architecture and Urban Design, 1989 (Online, in a much abbrievated form, at http://www.suisman.com). Also see John Kaliski, “The Form of Los Angeles’s Quotidian Millennium” in The Edge of the Millennium: An International Critique of Architecture, Urban Planning, Product and Communication Design edited by Susan Yelavich (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institute, 1993), pp 106-119. Research by the Planning Center in Orange County studied the viability of converting commercial corridors into housing sites from a design perspective, and a 14 June 2002 Solimar Research Group brief authored by William Fulton confirms that this conversion is in fact taking place. The City of LA’s General Plan Framework, adopted in 1996/2001, promotes mixed-use corridors (see, for example, this drawing), but it is only recently that zoning codes have caught up with policy. See Ordinance No. 174999 Residential/Accessory Services Zone, reported by Jocelyn Stewart, “The Sky’s the Limit with New Zoning,” Los Angeles Times, 29 Nov 2002 and Howard Fine, “City to Ease Way for Residences in Business Districts,” Los Angeles Business Journal, 2 Sept 2002.

[10] The proliferation of housing without street-facing retail is an equal failure of urban imagination, but that is the topic of yet another essay.

[11] For a more extended critique of CityPlace, see Michael Bohn, “The Good, the Bad, and the Monotony” in this edition of the LA Forum newsletter. For Paseo Colorado, see Nicolai Ouroussoff, “Pasadena’s Paseo Colorado: Shopping for Reality, in Vain,” Los Angeles Times, 9 Nov 2001. For a general critique of new pedestrian malls, see Nicolai Ouroussoff, “No Sale in a Faux Town,” Los Angeles Times, 27 Jan 2002.

[12] Jesus Sanchez, “An Upscale Urban Village Emerges in Genteel Pasadena,” Los Angeles Times, 30 Nov 2002 and Marshall Allen, “Living Large in Pasadena,” Pasadena Star News, 16 Sept 2002. Both articles note the significant dollar premium paid for such “urbane” living and the affordable housing gap this presents. Recent plans for Santa Monica Place also propose to “invert” the mall and top it with housing: see Carolanne Sudderth, “One Little Shopping Mall and How it Grew and Grew and Grew,” Ocean Park Gazette, 5 June 2002.

[13] Danny King “Trizec Said Near Sale of Successful Pasadena Project,” Los Angeles Business Journal, 2 Sept 2002 and “Developers Diversified Realty Announces Acquisition of Paseo Colorado Shopping Center”, 16 Jan 2003. DDR, curiously, is also the developer/owner of CityPlace and The Pike in Long Beach. The housing component of Paseo Colorado is owned by Post Properties and was not part of the sale. TrizecHahn developed both Paseo Colorado and Hollywood&Highland the latter project, with an exclusive focus on tourist-oriented entertainment/retail, has been a financial loss.

[Image Credits] Historic Farmers Market photographs from the Whittington Collection, Department of Special Collections, University of Southern California, published in Richard Longstreth, City Center to Regional Mall, MIT Press, 1997. Photographs of The Grove by Juan Gomez-Novy and Alan Loomis. Paseo Colorado photograph by Ehrenkrantz Eckstut & Kuhn; HortonPlaza by The Jerde Partnership; Hollywood & Western by Hollywest Promenade.